Stop Beginning At The End!

Portraits are some of the most striking pieces in colored pencil. When done well, the realism is breathtaking!

I can’t count the number of times I’ve heard someone say, “Is that colored pencil? But the people look so real! I didn’t know colored pencil could do that.”

Many artists (myself included) see colored pencil portraits and feel inspired to draw one themselves. They race off to the bookstore or start searching YouTube for a great tutorial, then wonder why their portraits fall short.

Why don’t my colored pencil portraits look realistic? Where did I go wrong? Can I even learn how to do this? What am I missing?

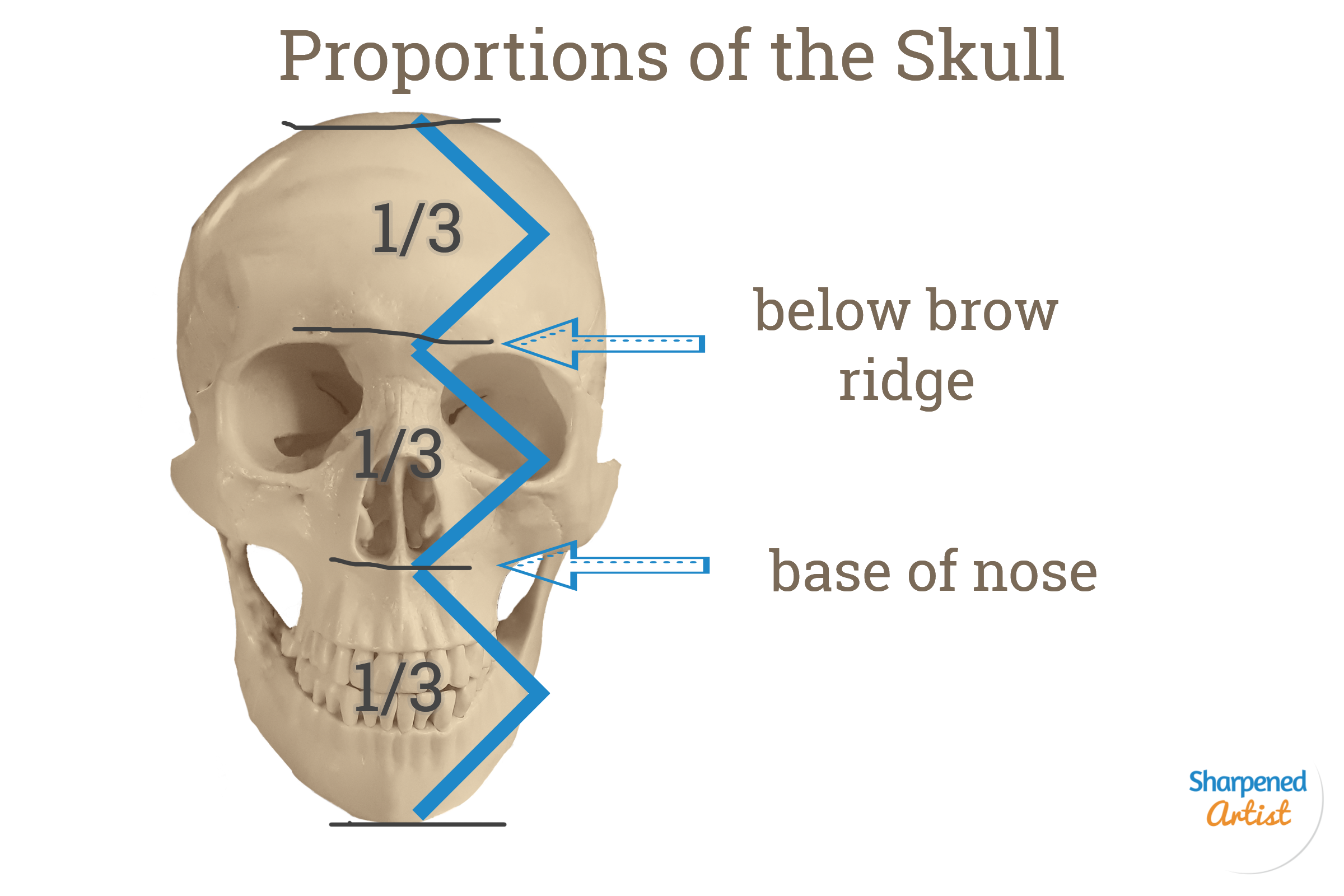

That last question is the most important! Most portrait tutorials are missing some of the most fundamental information needed to draw a truly realistic portrait: anatomy of the skull and face, angle and positioning variations, ideal proportions, and more.

It took me an embarrassingly long time to figure this out for myself.

But once I headed back to the beginning and did some of the necessary pre-work, I became comfortable with portraiture and began loving the results. My portraits started to come alive the way I had always wanted plus I was way more confident throughout my drawing process. I actually enjoyed the process!

That’s what I want for YOU. And, yes, it IS possible for you!

Welcome to the Portrait Prep Drawing Series!

In this series of lessons, I want to lead you through the all-important fundamental information. If you’re anything like me, you might think you can skip all of this stuff.

How to draw a line?? Anatomy? Head construction? Sounds like a waste of time-- I’ll just study photography and find great reference photos instead.

Not so fast, my friend! Learn from my mistakes, and begin at the beginning.

To create an appealing house, it’s essential to first build the frame before putting up the walls, painting, and decorating, right? Portraits are no different. To create a realistic portrait, you have to understand the underlying structure of the head before rendering the skin and hair and other features.

Follow along through the next few posts as I share with you some of the information I wish I’d had when I started drawing portraits. By the time we’re through, I want you to be so familiar with every possibility (face positioning, angles, and foreshortening of the features) that when you finally pick up your colored pencil, you will be ready to paint that final layer on a well-constructed head.

This article is the introduction to the Portrait Prep Drawing Series! Here’s the link to the first installment in this drawing series!

Want an even deeper look at drawing portraits? Sign up for my FREE Portrait Prep Drawing Course!

Portrait Prep is a video course inside the Sharpened Artist Academy. Together we’ll walk through the core fundamentals of drawing incredible portraits.

Sound good? Click here to signup

What are your biggest challenges when drawing colored pencil portraits? Share in the comments below!